We Wrote the Book On It

07.25.19 · Sonia Greteman

Kansas aviatrix Amelia Earhart once famously said, “The most effective way to do it, is to do it.” We recently took that advice.

We decided to publish a book about the Air Capital, Wichita: Where Aviation Took Wing. The creative assets already existed. We’d developed them over a 10-year period for a large-scale history display at Wichita Eisenhower National Airport’s new terminal. Its opening in 2015 drew raves. But four years later, lacking a benefactor to fund the book’s creation, we are taking it on ourselves.

Wichita: Where Aviation Took Wing is now available for preorder.

The Air Capital’s stories haunted us. After living with them for so long, we felt responsible. To live on, stories need to be shared. The display on the terminal’s mezzanine draws lots of attention. But busy travelers only have so much time. We want people to hold these stories in their hands. To curl up with them. To come back again and again.

Dreams of Flight

Today, when flying on a $60-million jet at 40,000 feet with fly-by-wire precision, it’s easy to forget the early birds. And the men and women who risked all to test their limits. More than a century ago, Kansas visionaries and likeminded innovators dreamt of flight. Amateur engineers across the state drew up daring plans. Some put hammer to nail and built their flying contraptions. Nothing stopped their pursuit. Here’s a small sampling of what our book offers.

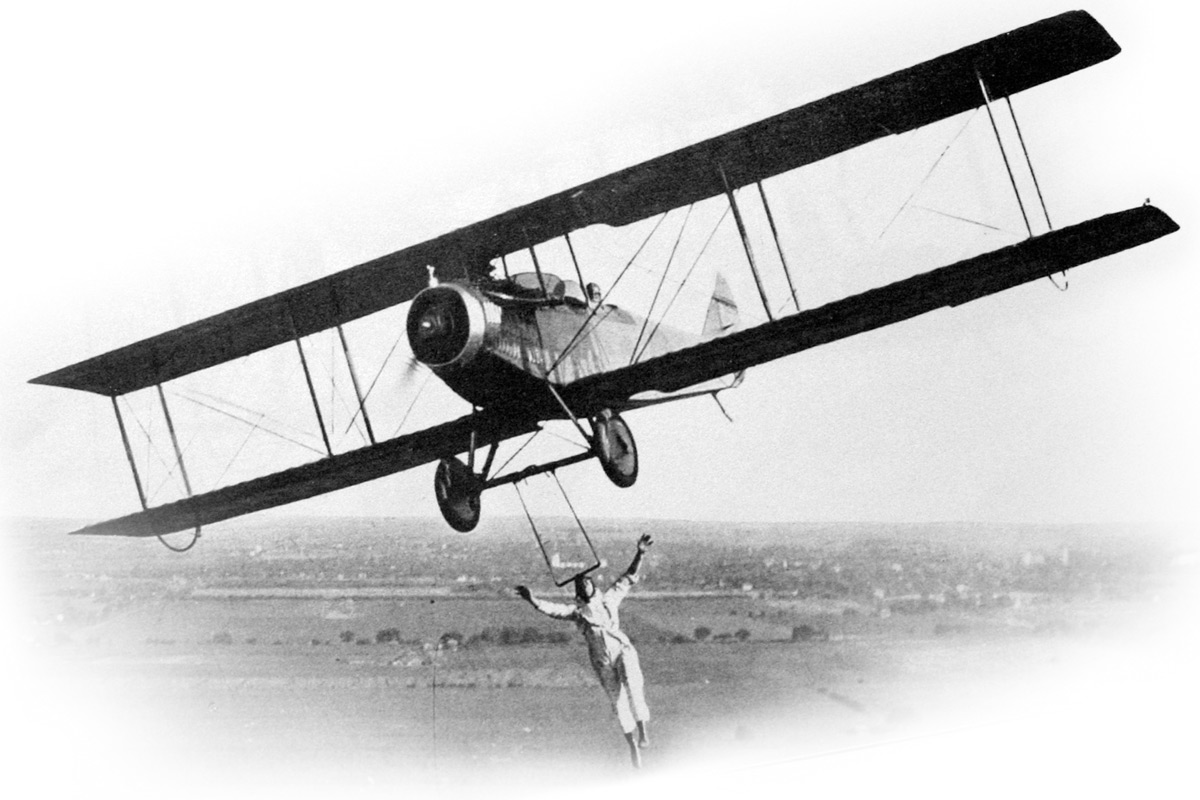

of the Horchem Aerial Show hanging on by his teeth.

More Ideas Than Money

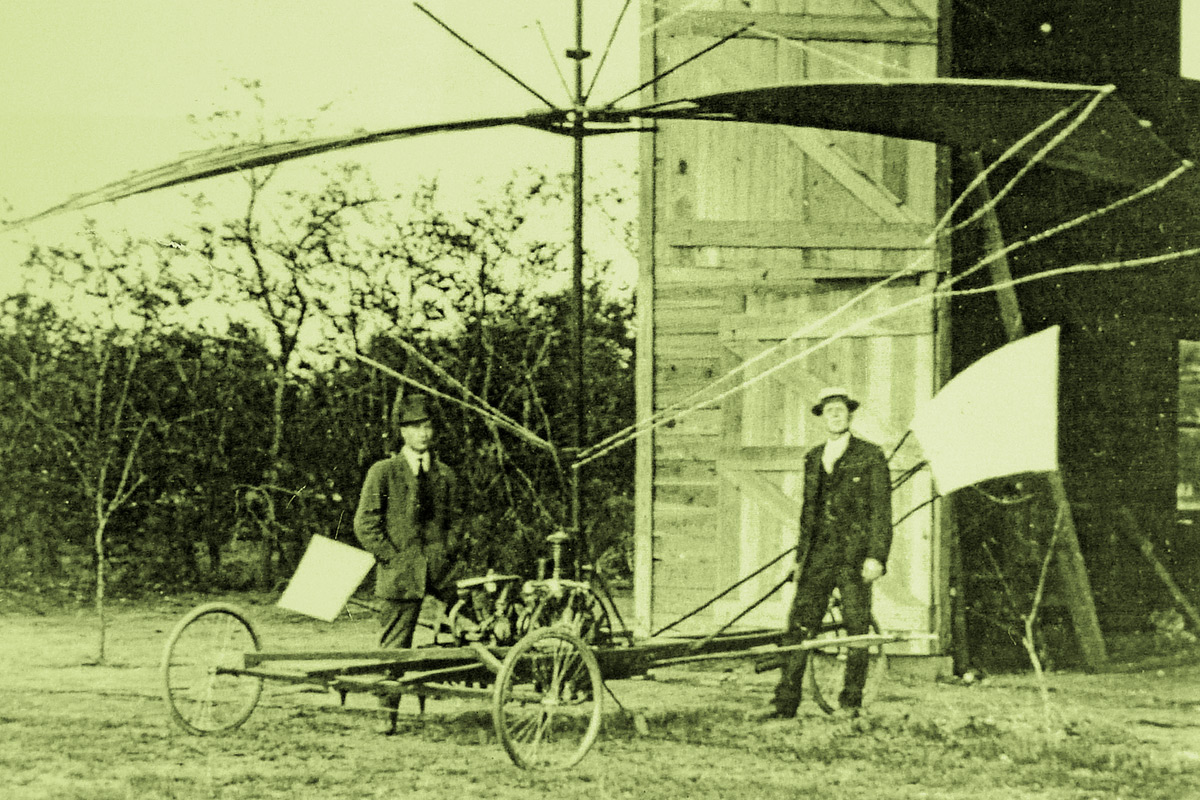

Before the Wright Brothers got off the ground in 1903, Carl Dryden Browne built a flying-machine factory in Freedom, Kansas. He earned the first U.S. rotary-wing aircraft patent. Lack of funds caused his factory to fold.

In 1909, William Purvis and Charles Wilson of Goodland drafted one of the earliest helicopter designs. It may have eventually flown. But again, their dreams were bigger than their resources.

The Henry Ford of the Air

On Sept. 2, 1911, Albin Longren became the first person to build and fly an airplane in Kansas. His pusher-type biplane lifted off from a hayfield southeast of Topeka with a four-gallon gas tank, a pocket watch and barometer that served as his flight instruments. Despite the fact he had never flown, Longren made eight successful flights the first day. He went on to careers in barnstorming, aircraft design and manufacturing, earning the nickname “The Henry Ford of the Air.”

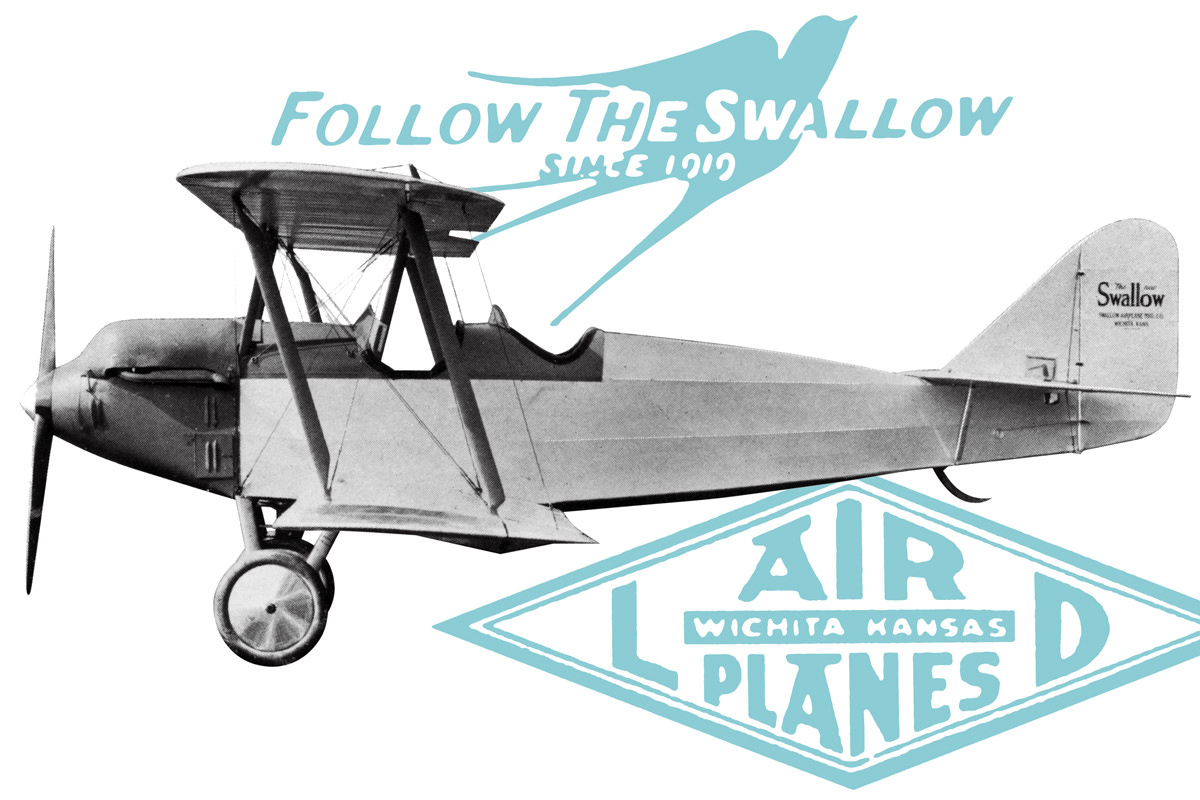

The first plane built in Wichita rolled out of production in 1917, when Clyde Cessna assembled his Comet. Wichita’s first commercial aircraft, the Swallow, came from the E.M. Laird Airplane Co. in 1920. By 1928, Wichita was general aviation’s manufacturing grand central, producing 120 airplanes a week – a quarter of all U.S. output. A Chamber of Commerce Air Capital logo contest celebrated the city’s 16 aircraft manufacturers, six aircraft engine factories, 11 airports and dozen flying schools.

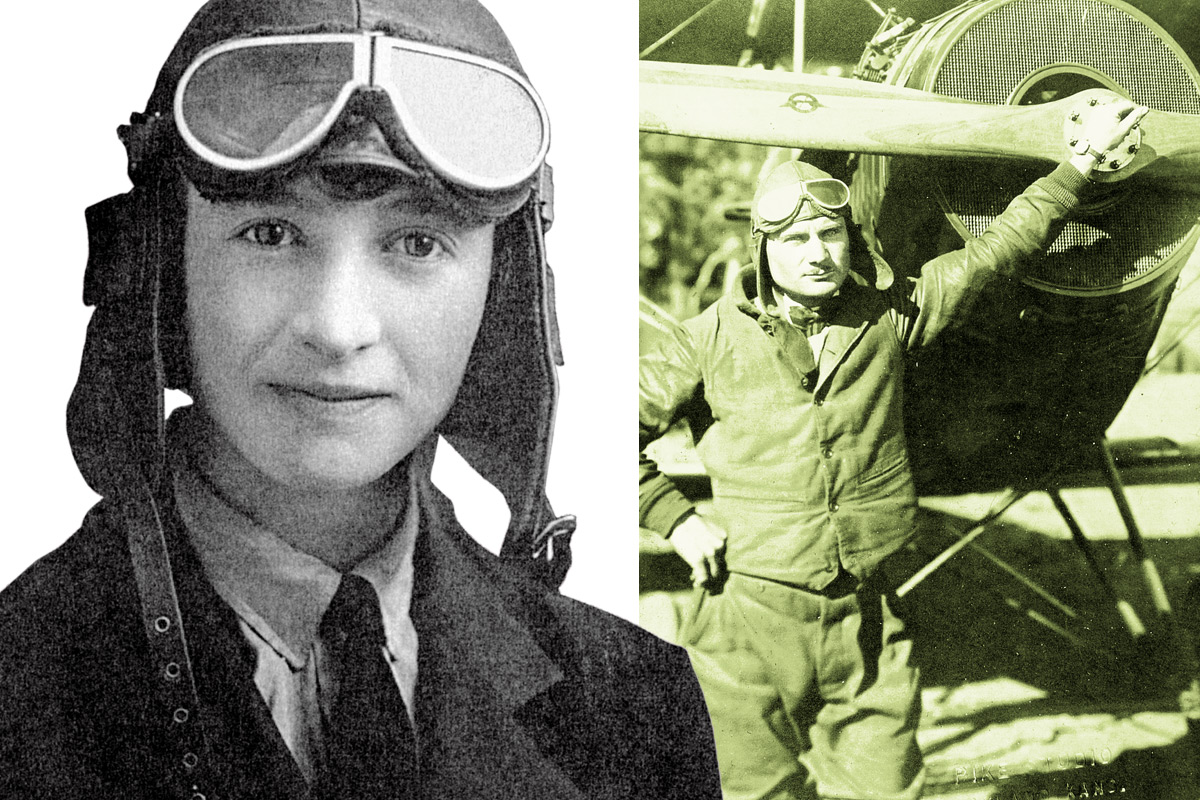

The Demanding Father of Wichita Aviation

One of the most influential of these early birds was neither an aircraft designer nor a pilot; he was a wealthy oilman by the name of Jacob “Jake” Moellendick. As one of general aviation’s earliest venture capitalists, he was adamant about the influential role flight would play. In the 1910s and ’20s, he sunk every penny of his vast wealth into the advancement of Wichita aviation. He died in 1940 without enough cash to pay for his funeral. But he left a rich legacy. Bringing together E.M. “Matty” Laird, Lloyd Stearman and Walter Beech then bankrolling their ideas – gave birth to the E.M. Laird Airplane Co. – and Wichita aviation.

Barnstormers Shut Down Towns

With aircraft came the death-defying daredevils who flew them. Performing gasp-inducing spins and dives. Flying upside down. Wingwalking. Changing planes in midair. Swinging from trapezes mounted to the landing gear. There seemed to be nothing they wouldn’t try. As early as 1910, crowds gathered across Kansas to marvel at these new machines. And to thrill at the ever-present possibility of a crash. By the 1920s, barnstorming was a major source of entertainment – part technological wonder, part Roman Coliseum.

Birdie and the Flying Squirrel

Many barnstormers worked as teams in flying circuses, complete with booking agents. The much beloved husband-wife duo Cyle “The Flying Squirrel” and Bertha “Birdie” Horchem used the tagline, “If done in the air, we do it.” And they did.

Cyle, a WWI Army pilot, became a world champion upside-down flyer. Birdie held the women’s altitude record (16,300 feet). She could do 15-25 consecutive loops as well as a 2,000-foot tailspin. They did loop-the-loops with trails of fire. Shot fireworks from their Wichita-built, fabric-and-wood Laird Swallow. From their home in Ransom, Kansas, their air circus traveled the country, amazing crowds nationwide.

Birdie died in a plane crash at age 24. The brokenhearted Cyle became increasingly fearless. Eight months later, at age 26, he slipped and fell to his death as he climbed onto the plane’s wing.

Why Wichita as Air Capital?

Flat prairies resembled one enormous landing field. Southwesterly winds added thrust to get and stay aloft. Farming and small manufacturing provided a legion of imaginative, industrious problem-solvers. Local boosters latched onto and promoted anything that flew. The city’s central location provided an ideal refueling stop for coast-to-coast airmail routes. And oil generated a class of savvy, starry-eyed entrepreneurs who both used aircraft and had money to invest. Wichita brought it all together. The people. The promise. The planes.

A Story Worth Telling

Wichita: Where Aviation Took Wing takes readers from the early birds to the pioneers who established dozens of aircraft and associated factories in the 1920s. The story continues with the founding of Cessna, Beechcraft, Stearman (which became Boeing Wichita, then Spirit AeroSystems), and Mooney. The massive build-up during World War II transformed our city – and aviation. Robust post-war growth got another boost when Bill Lear came to town and launched the business jet revolution with his Learjet.

Wichita produces more airplanes – almost 300,000 to date – and offers more skilled aviation workers than any other city. It has delivered more than half of all the general aviation airplanes ever built. Today Wichita remains at the center of global aviation design and manufacturing with Spirit AeroSystems, Textron Aviation, Bombardier Learjet, Airbus and many dozens of aviation manufacturers, suppliers and support organizations. Aviation forms Wichita’s heritage and future. We worked with these manufactures to source stories, double-check facts and align nuances in interpretations, memories and records.

To Advance, We Remember

This book reminds us where we’ve been. And inspires us to push on. Our agency is donating creative services and underwriting production fees. Donlevy Lithograph is printing at cost – all to make this book happen. We hope you’ll preorder your copy now at WichitaAviationHistory.com. Books publish in early September. Consider it our gift to a beloved industry and community.

This column originally appeared in the July 25, 2019, issue of BlueSky News.